Research activities

Close-up

Learn about the lives of people "behind the words" from the letters of haiku poets

Faculty of Intercultural Japanese Studies Graduate School of Graduate School of Comparative Culture

Naoko Tsujimura Associate Professor

Research topic: Japanese literature Early modern literature Haiku literature

What is Haikai? Poetry is born from play.

During the Edo period, haiku was called "haikai." Today, haiku refers to short poems with 17 syllables in the "5-7-5" pattern, but in the Edo period, haikai also popularized "renku," which repeats the "5-7-5" and "7-7" patterns and strings together a set number of lines (such as 100 or 36 lines). Basho also performed renku in the various places he visited on his travels.

The fun of renga is that everyone strings together verses to create a single work. You might think of a work as having a consistent theme or story, but that's not the case with renga. With each verse, the characters and scenes change, and a new world unfolds. Unlike waka, haikai also uses everyday words and everyday life as its subject matter, so its world expands infinitely. With the next verse someone writes, unexpected stories are born one after another. In that sense, it may have felt a little like what we would now call a live performance, in that it cherished what could only be born because the members were gathered in that moment.

Haikai, which allows the mind to wander in the world of words, values the "spirit of play." The word haikai originally means "humor." The "kai" in haikai also means "harmony." It is a literary form unique in the world in which people enjoy creating with words in a harmonious conversation, rather than competing for merit.

The first 5-7-5 syllable in a renga is called a "hokku." This is the original form of haiku. It is a much shorter world of 17 syllables than the 31 syllables of waka and tanka. What's more, it even includes seasonal words. You might think that there are many restrictions, but the purity of cutting out all unnecessary things to the bare minimum, and the richness of the world that unfolds behind the pared-down expression, are what make it so appealing.

Basho is a charismatic figure who continues to fascinate people today and in the past.

Basho's famous haiku, "An old pond, a frog jumps in, the sound of water," and "The Narrow Road to the Deep North" are considered classics today, but in Basho's time, they were completely new works not found in haikai until then. It was Basho who elevated haikai to a literary genre comparable to traditional elegant literature such as waka and Chinese poetry. He was a pioneering innovator, pioneering the cutting edge of his time. As everyone knows, he possessed an exceptional sense of language and is known for his many famous phrases and quotes. The phrase "Futeki Ryuko" (unchanging and ever-changing), which Basho spoke to his disciples after his journey on the Narrow Road to the Deep North, represents Basho's haikai philosophy. Even today, it is interpreted in various ways, sometimes even as a philosophy of life. Perhaps the intrigue lies in the combination of polar opposites: "Futeki" (unchanging) and "Ryoko" (changing). Another saying is, "Newness is the flower of haikai." He continues to create new works, and yet his words, even today, more than 300 years later, still resonate with us with a timeless universality. This is the power of words.

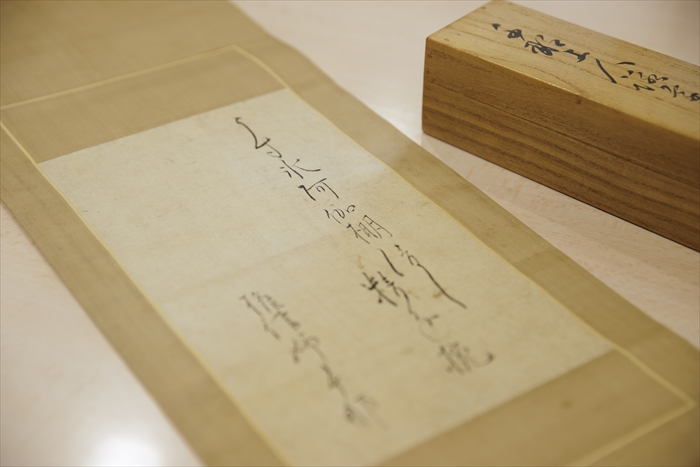

Basho died at the age of 51, but in a draft he left behind when he was nearly 50, he wrote, "I will never stop pursuing the path of haiku until I die." With only a little paper left, he wrote this in small but clear handwriting at the bottom. Basho devoted his life to haiku. What was it about haiku that so captivated Basho? Why are we so drawn to Basho's words? I would like to find out.

Through letters, we can learn about the inner workings of Basho and his disciples.

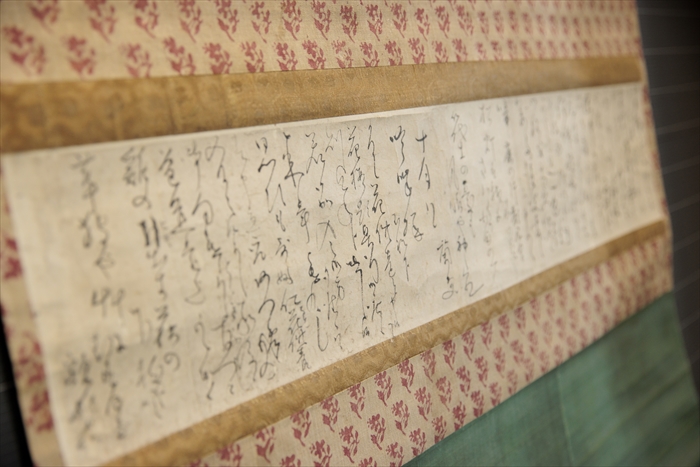

A valuable experience in advancing my research was the opportunity to come into contact with handwritten materials as a curator. The Kakimori Bunko (Itami City, Hyogo Prefecture) where I worked houses a large collection of haiku materials collected by Okada Rihei, a leading researcher in Basho's handwriting. The "Furuikeya" short poem and a clean copy of "Oku no Hosomichi" are both located at the Kakimori Bunko in the Hanshin area.

Of all the letters, Basho's were the ones that interested me the most. His letters reveal a variety of emotions, from eloquently proclaiming the ideals of haiku and expressing unreserved joy at the progress of his students to ruminating on the fact that pickles sting your teeth, to musing about how old you've gotten. Rather than a solitary figure who stoically pursued the path of haiku, we see Basho as a man among the people, sometimes even a little human. The brushstrokes and ink colors that can only be found in handwritten letters make me feel as though I've come into contact with the subtleties of Basho's soul.

From there, he became interested in studying letters, and now continues to decipher letters from Basho's disciples. Perceptions of Basho vary depending on each individual's background, such as their relationship with Basho, the generational gap, and the trends of the time. For example, Sugikaze, a disciple of Basho from the very beginning when he began his career as a haiku poet in Edo, lived on to the age of 86, 38 years after Basho's death, lamenting his aging. One by one, the friends who knew Basho passed away, but Sugikaze's letters reveal that until his later years, he treasured the words Basho left behind: "Make haiku your source of enjoyment in your old age." Furthermore, around the time of Basho's 80th anniversary, Buson spoke some very high-level words to his new disciples, saying, "You should aim to achieve a state of mind that transcends the worldly world of Basho's haiku, but you must not become a copy of Basho." What attracted each of them to Basho and what they valued? I believe that by clarifying this, the appeal of Basho himself will emerge.

Author

Naoko Tsujimura TSUJIMURA Naoko

Faculty of Intercultural Japanese Studies Graduate School of Graduate School of Comparative Culture

Associate Professor

Research Field

Literature/Humanities/Humanity/Psychology

Research Topics

Japanese Literature Early modern literature Haiku literature