Research activities

Close-up

"Hikikomori" as a Sociological Question

Faculty of Modern Social Studies

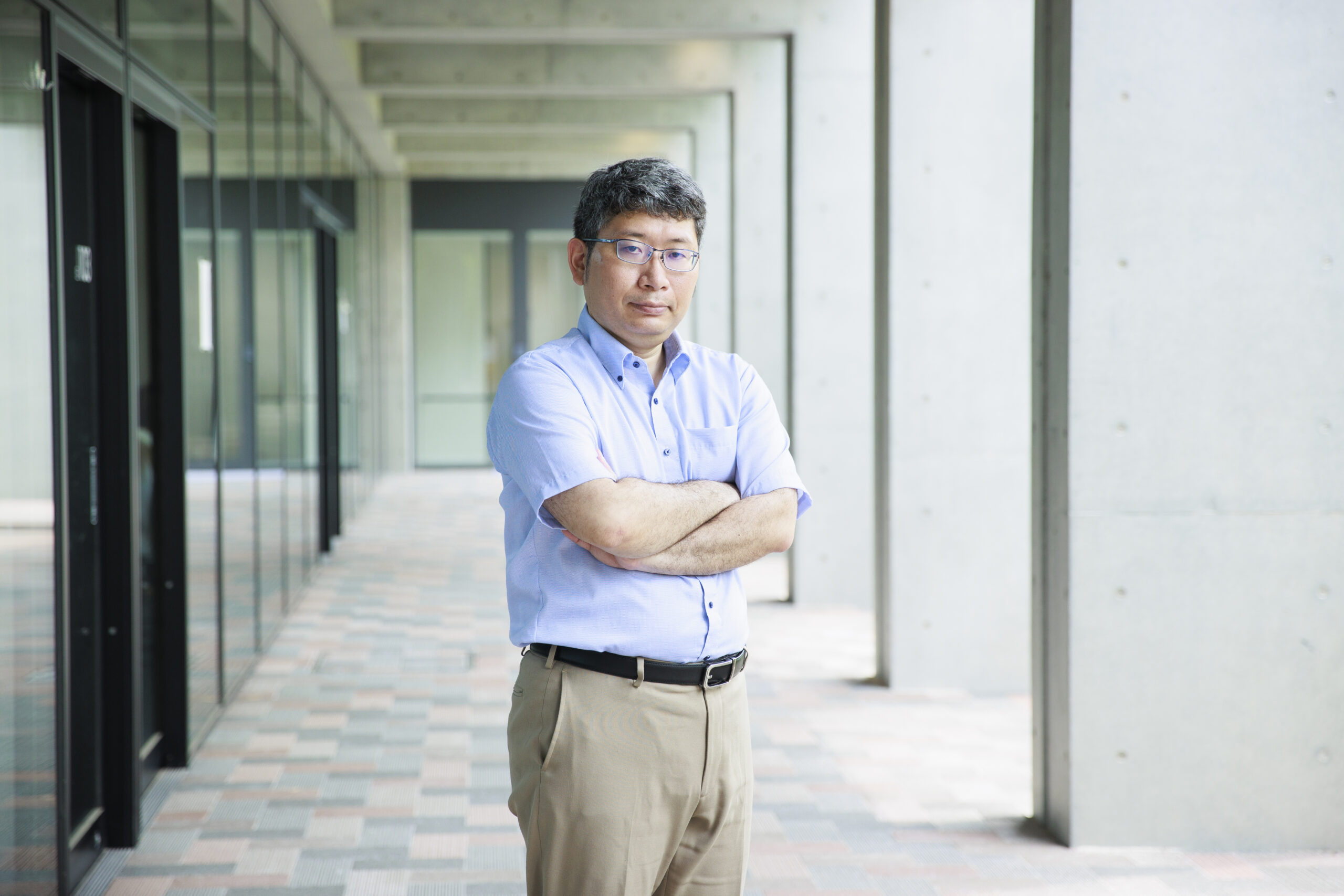

Kohki Itoh Associate Professor

Research Theme: Sociology Social Issues Community Studies Social Research Methods School refusal/reclusion

Until attention was paid to the social background of hikikomori

Many people still have the misconception that "hikikomori is spoiled" or "people become hikikomori because they are weak", but we need to look at the social system in which the way we judge others makes people hikikomori. Hikikomori started to attract social attention in the late 1990s, but it was also considered a problem in the context of school refusal (also called "school refusal"). Until around the 1960s, the term "school phobia" was used, but ultimately, it was the view of those around the person that "it is a problem of the person who cannot adapt to the group called "school". This framework of view itself was also used in "hikikomori", which later began to be treated as a social problem. In "hikikomori", words such as "human relationships", "communication", "employment", and "local community" were used instead of "school", and the problem was the inability to adapt to such places and relationships.

On the other hand, what kind of characteristics does the side that looks at this person in this way (= Japanese society) have in the first place? We can point out the existence of a normative consciousness (conformity pressure) that demands extreme homogeneity in certain aspects of people's lives. Since conformity pressure is invisible to begin with, let's visualize it based on some examples. For example, in the workplace, Japan has had a long-standing practice of mass hiring of new graduates, lifetime employment, and seniority-based promotion. Even now, many students are trying to use the card of being a new graduate when job hunting. In the field of education, the tendency to group people according to the same age is still strong. In terms of statistical data, for example, the distribution of ages at university entrance and the rate of births out of wedlock can be interpreted as being extremely homogeneous compared to OECD countries. As a result of this normative consciousness that demands homogeneity in education and marriage, the average age at university entrance ranges from 19 to 25 years old in OECD countries, while in Japan it is roughly 18 to 19 years old. While the rate of births out of wedlock has increased significantly in many countries over the past 50 years, in Japan it has only increased by about 1 percentage point. Although it is rarely used these days, the phrase "one hundred million middle class" itself symbolically expressed the normative tendency in Japanese society to seek a high level of homogeneity.

Thirty years have passed since "hikikomori" began to be treated as a social problem. During this time, people and lifestyles that had not previously been visible have become socially apparent not only as horizontal diversity but also as vertical disparities. While there are areas where conformity pressure is strong as mentioned above, the need for social action has become louder in areas such as poverty, social exclusion, discrimination, and minorities. It seems that we are finally beginning to realize the mechanisms that drive people into hikikomori in Japanese society.

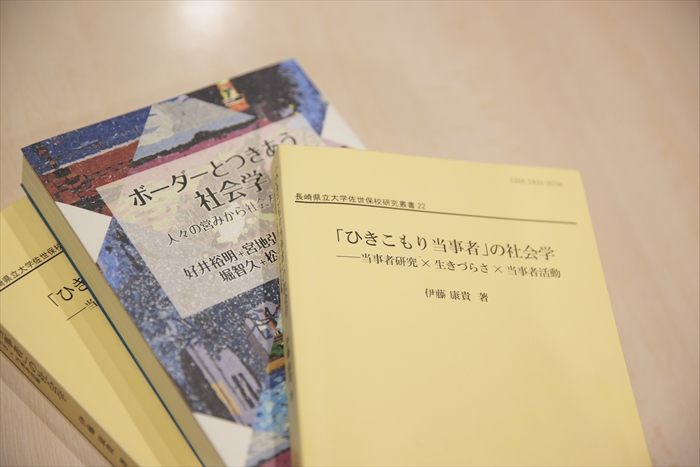

What I learned by looking back as a person involved

In my case, I decided to look back on my experience not only as a "person involved" but also through the lens of "sociology." The "lens of sociology" is a somewhat difficult expression to grasp, but in essence, I think it refers to the attitude of looking back on my own experience of hikikomori from various perspectives using sociological theoretical frameworks and empirical data (statistical data, data obtained from interviews, participant observation, etc.) and linking it to social structures. I believe that "studying sociology" or "doing sociology" is precisely about acquiring and practicing such an attitude. By doing so, I believe I was able to consider my own "difficulty in living" from a bird's-eye view and multiple perspectives, without viewing my experience as absolute, and while keeping a good distance from it.

For example, I once wrote an autobiography for my graduation thesis, looking back on my own experience of social withdrawal. Writing down your experiences in this way can also serve as an opportunity to relativize your own experiences and question your own existence. It can also be a foundation for starting a dialogue (sociology is part of that dialogue) by comparing and relating yourself to others. Giving order in the form of language to your own chaotic experiences can also help you tame the discomfort of living.

I also think it is important that such reflection does not end with a single session, but is constantly updated. New realizations can come from encounters and conversations with others, and new perspectives can come from aging and changes in one's own body and relationships with others. Also, the way one directs one's consciousness and perspective in life can change depending on the place and region in which one lives.

In my case, in 2018 I married a woman who had also been a hikikomori for about 12 years, and at the same time I got a job at a university in a rather rural area of Kyushu, so we moved together. Living together in a new community in an unfamiliar place with a culture different from Kansai did not destroy my common sense (including sociological ones), but it did force me to re-examine it. I have recently written a number of articles about the events that have occurred during this time, and in a sense I consider these to be an update of my own autobiography, and therefore the beginning of a new sociology for me. As a person involved and as a sociologist, I have come to see that "the questions about human beings are endless."

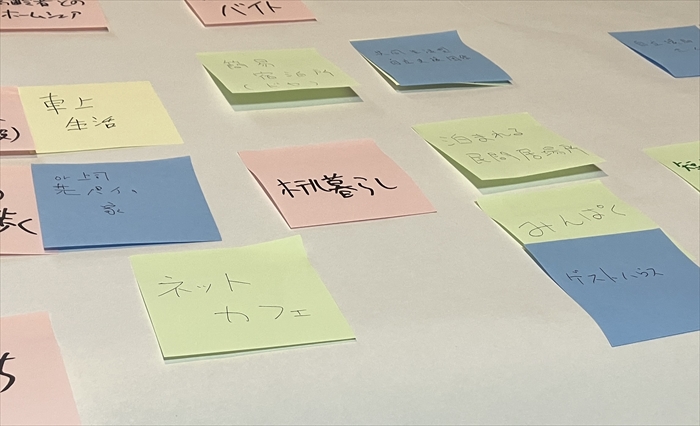

The significance of communicating through dialogue with the parties involved

To be honest, even though we say "people involved," there were many different ways of being. They did not have exactly the same experiences. While there were some overlapping experiences, there were also differences. It's a very obvious thing, but before I started my research, I was dragged down by the social image attached to the word "hikikomori." Actually coming into contact with the appearances and stories of various people involved in fieldwork made me rethink a lot of things. When I was young, I originally envisioned an easy-to-understand goal such as employment or recovery of interpersonal relationships. However, through fieldwork, I realized that the fact that I thought (or could think) that way was proof that I was in a kind of privileged position, and that there were people who did not think that way (especially those who had been withdrawn for a long time) and that the goal was not the goal at all (rather, the difficult situation of life and existential suffering continued even after that).

Of course, it is true that within the category of people with disabilities, being "same yet different" or "different yet the same" creates a certain sense of solidarity. Subtle differences create dialogue and also conflict. Since it is a dialogue that puts one's existence on the line, it is inevitable that conflicts will arise, but as a way to avoid such conflicts, for example, in self-help groups and other activities for people with disabilities, there are rules such as "first listen to what the other person has to say and do not reject it." In fact, there are similar warnings in the interview methods used in social surveys, and some stories are created by setting such rules. Through such fieldwork, I found it very meaningful to be able to come into contact with the alternative stories of people with disabilities and to closely observe the process of them regaining their subjectivity of "talking about themselves." The process of change in people is something that can be overlooked if you do not pay attention to it consciously, so by approaching such things from a person-research and sociological perspective, I was able to make a conscious observation.

On the other hand, some people who have reached the "next step" in regular or intermediate employment face new difficulties in life. Not only are there difficulties in the workplace, such as a lack of understanding, harsh human relationships, and long working hours, but also in family situations, such as no change in difficult relationships with family members to begin with, or new issues with caring for family members. Some people also lose their cool when financial and other worries about life are added to the mix. In the end, I think the problem lies not in "hikikomori" itself, but in the structure of the society in which we live. I think it is the difficulties that arise in life and the lack of social support and understanding for these difficulties that ultimately lead people to express the term "hikikomori."

Sociology is a discipline that questions how we live

It is quite difficult to give a clear answer to "this is what hikikomori is" from a sociological standpoint, but I personally think that dealing with "hikikomori" as a sociological question was quite meaningful, because the phenomenon of "hikikomori" itself requires sociologists to look at things from multiple angles.

Hikikomori is not just a disease or a disability, but requires a broader perspective, including individual identity, communication with others, family and community, social policies and the state of the nation, youth culture, self-expression, and social movements. While I have taken hikikomori as my theme, I think I have used it as a starting point to approach the diverse and complex structure of modern society. From a micro perspective, hikikomori itself shows diverse and individualized individuals with different classes, regions, eras, thoughts and hopes about life and daily life. However, despite such diversity, hikikomori has become a macro social phenomenon of a certain common state of hikikomori, affecting millions of people, and I think this is what makes hikikomori interesting as a sociological question.

And, in the end, it's really interesting for me to hear what the people involved have to say. Being a hikikomori means distancing yourself from what society considers normal. By doing so, you protect yourself, take a break, worry, try and fail, and the meaning of being a hikikomori varies from person to person, but in any case, it is not common sense behavior from the perspective of the general public (so it is looked down upon). However, sociology also has a similar aspect, and it is often said that sociology is an academic field that "questions common sense" and "thinks at a distance from what society takes for granted." So, in a sense, being a hikikomori is like doing sociology. When I listen to the stories of people involved in interviews, there are often moments when I feel sociological implications based on their lives and thoughts from their words and appearances. If you delve into such implications sociologically, you can see the social mechanisms of the difficulties we have in living on a daily basis. I think this is true not only for "hikikomori," but also for themes related to the difficulties of living for minorities. I believe that the greatest appeal of sociology is that it allows us to question "how humans live" from such perspectives.

Author

Koki Ito ITO Koki

Faculty of Modern Social Studies

Associate Professor

Research Field

Society and Information

Research Topics

Sociology Social Issues Community Studies Social Research Methods School refusal/reclusion